Iron magnetism matters more than most people expect in real engineering, especially when parts move from design into real manufacturing environments. As a CNC machining and die casting manufacturer, we see this misunderstanding frequently across sourcing and inspection stages.

You may test a part with a magnet and feel confident, then discover later that heat, forming, or alloy changes make the result inconsistent. That confusion creates sourcing mistakes, sensor issues, messy chip handling in CNC machining, and avoidable disputes about “wrong material” in incoming inspection. It also makes people overgeneralize from “iron” to “steel” or “stainless,” which often behave differently.

In this guide, you will learn whether iron is magnetic, why it behaves that way, when it changes, and how to apply that knowledge in design, manufacturing, and purchasing decisions.

Is Iron Magnetic?

Is iron magnetic under normal conditions

Yes, iron is magnetic under normal conditions. At room temperature and in everyday environments, iron strongly interacts with magnetic fields. A standard permanent magnet will attract iron immediately, which is why iron is often used as a reference material when people test magnetism in workshops, factories, or laboratories.

This behavior is stable in most practical situations. Structural iron parts, iron-based machine components, and raw iron stock all show clear magnetic attraction during handling, inspection, and machining. In manufacturing environments, this predictable response enables magnetic clamping, chip separation, and material identification. However, this “normal condition” assumption only holds when temperature, processing history, and composition remain within typical industrial ranges.

Why iron is classified as a ferromagnetic material

Iron is classified as a ferromagnetic material because its atomic structure allows strong and cooperative magnetic alignment. Each iron atom contains unpaired electrons whose spins can align in the same direction. These aligned spins form regions called magnetic domains, which collectively generate a strong magnetic field when influenced by an external magnet.

Unlike paramagnetic materials, which respond weakly, iron’s domains reinforce one another instead of canceling out. This property gives iron high magnetic permeability, meaning it concentrates magnetic flux efficiently. According to standard materials science references such as Encyclopaedia Britannica and Wikipedia, iron’s ferromagnetism places it in the same fundamental category as cobalt and nickel, the three most common ferromagnetic metals used in engineering and industry.

Situations where iron may lose or weaken its magnetism

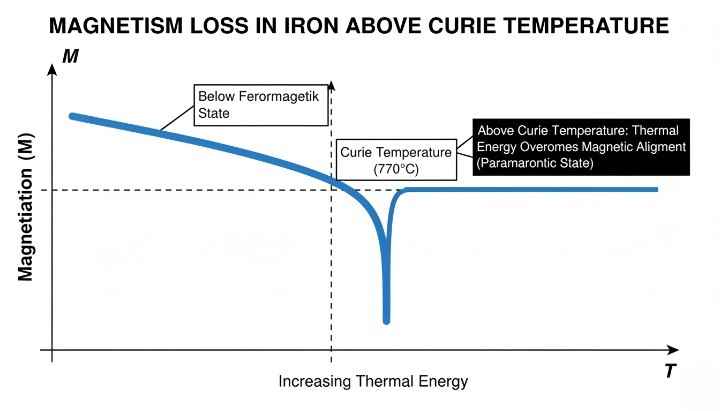

Iron does not remain magnetic under all conditions. High temperature is the most common factor that removes magnetism. When iron exceeds its Curie temperature, approximately 770 °C, thermal energy disrupts domain alignment and the material becomes non-magnetic until it cools below that threshold.

Mechanical deformation and heat treatment can also change magnetic behavior. Cold working, welding, or certain annealing processes may reduce or redistribute residual magnetism. In addition, alloying iron with elements such as nickel, chromium, or manganese can weaken or fundamentally change its magnetic response. These effects matter in CNC machining, die casting, and inspection processes, where a part’s magnetic behavior after processing may differ from its raw material state.

What Makes Iron Magnetic?

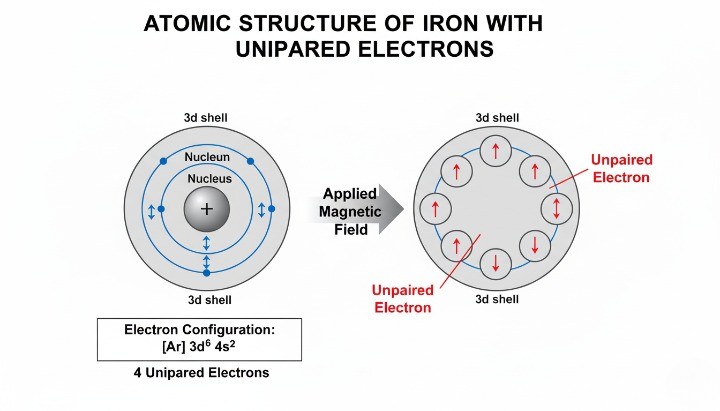

Atomic structure of iron and unpaired electrons

Iron’s magnetism starts at the atomic level. Each iron atom contains unpaired electrons in its outer electron shells. These electrons have a property called spin, which creates a tiny magnetic moment. In many materials, these moments cancel each other out. In iron, they do not.

Because of iron’s specific electron configuration, these magnetic moments can align instead of opposing one another. This alignment potential is what makes iron fundamentally different from non-magnetic metals like copper or aluminum. From a materials science perspective, this atomic structure gives iron the capacity to become strongly magnetic, even before any external magnetic field is applied.

Magnetic domains and domain alignment

Iron atoms do not align randomly across the entire material. Instead, they form magnetic domains, which are microscopic regions where many atoms share the same magnetic orientation. In an unmagnetized piece of iron, these domains point in different directions, so their magnetic effects cancel out overall.

When an external magnetic field is applied, many of these domains rotate and align with the field. As more domains point in the same direction, the material develops a strong net magnetic field. This domain-based behavior explains why iron can switch quickly between weak and strong magnetism depending on its environment and processing history.

Ferromagnetism vs other types of magnetism

Iron belongs to a category called ferromagnetism, which represents the strongest and most useful form of magnetism in engineering. Ferromagnetic materials can retain magnetization after the external field is removed, at least temporarily.

This behavior differs from:

-

Paramagnetic materials, which respond weakly and only while a field is present

-

Diamagnetic materials, which slightly repel magnetic fields

Only a few elements exhibit true ferromagnetism at room temperature, mainly iron, cobalt, and nickel. This limited group explains why iron remains so central to electrical systems, motors, and magnetic tooling.

Why iron responds strongly to external magnetic fields?

Iron responds strongly to external magnetic fields because its domains align easily and reinforce one another. The energy required to reorient these domains is relatively low, which allows iron to concentrate magnetic flux efficiently.

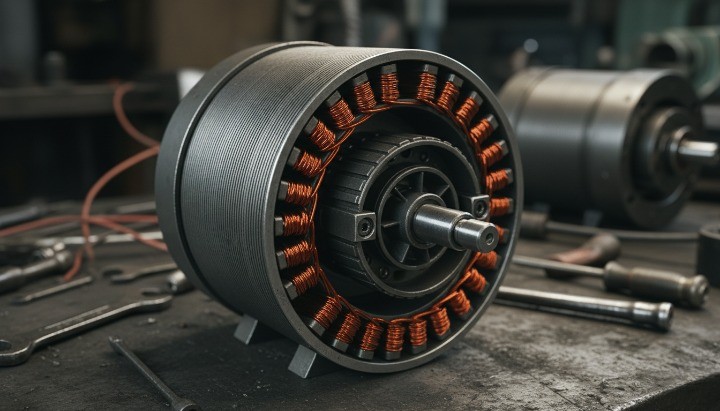

This property gives iron high magnetic permeability, meaning it channels magnetic fields instead of resisting them. In practical terms, this is why iron cores amplify magnetic fields in transformers and motors, and why iron components interact so reliably with magnets in manufacturing environments. The same responsiveness also explains why residual magnetism can appear after machining, forming, or inspection processes.

Magnetic Properties of Iron

Ferromagnetic behavior explained

Iron exhibits true ferromagnetic behavior

In practical terms, ferromagnetism explains why iron parts stick firmly to magnets, why iron cores intensify magnetic fields, and why residual magnetism can remain after processing. This property makes iron indispensable in electrical, mechanical, and industrial systems where controlled magnetic response is required.

Magnetic permeability and why it matters in engineering

Magnetic permeability measures how easily a material allows magnetic fields to pass through it. Iron has very high magnetic permeability, especially compared with non-magnetic metals such as aluminum or copper. This allows iron to concentrate and guide magnetic flux efficiently.

For engineers, permeability directly affects performance. High-permeability iron improves efficiency in transformers, motors, relays, and electromagnetic actuators. In manufacturing, it also influences magnetic clamping strength, sensor accuracy, and chip control. A material with unpredictable permeability can cause unstable performance in automated systems.

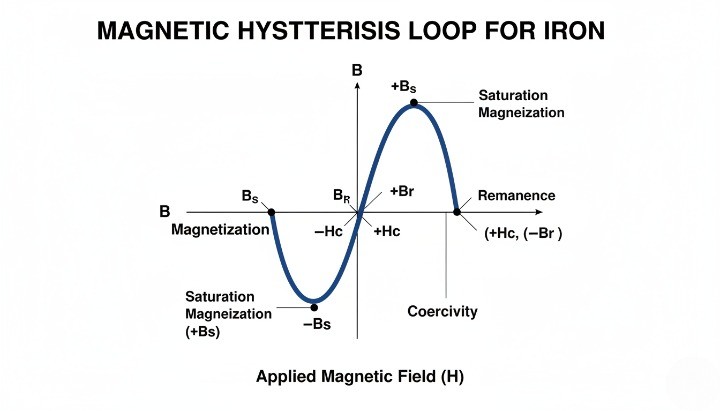

Magnetic hysteresis and remanence

When iron is exposed to a magnetic field and the field is later removed, the material does not return instantly to a neutral state. This lag is called magnetic hysteresis. The remaining magnetism is known as remanence.

Hysteresis explains why iron can hold residual magnetism after machining, inspection, or handling with magnetic tools. From a design perspective, hysteresis losses also matter. In electrical applications, repeated magnetization and demagnetization generate heat and reduce efficiency. Engineers must balance magnetic strength with acceptable energy loss.

Temporary vs residual magnetism in iron

Iron typically exhibits temporary magnetism, meaning it becomes magnetic in the presence of a field and weakens once the field disappears. However, residual magnetism often remains due to incomplete domain randomization.

This residual effect is usually small but can create real problems. Magnetized parts may attract chips, interfere with sensors, or cause assembly issues. In CNC machining and inspection, manufacturers sometimes demagnetize iron components intentionally to avoid contamination or measurement errors.

How purity and composition influence magnetic strength?

Purity plays a critical role in iron’s magnetic performance. High-purity iron shows stronger and more predictable magnetism because impurities disrupt domain alignment. Carbon, sulfur, and alloying elements introduce lattice distortions that reduce magnetic efficiency.

This is why electrical-grade iron and soft magnetic materials are tightly controlled for composition. In contrast, structural or alloyed iron sacrifices magnetic performance in exchange for strength, corrosion resistance, or manufacturability. Understanding this trade-off is essential when selecting materials for magnetic-sensitive applications.

Various Forms of Iron and Their Magnetic Properties

Pure iron and its magnetic characteristics

Pure iron displays the strongest ferromagnetic response among iron-based materials. Its low impurity content allows magnetic domains to align easily, resulting in high permeability and low hysteresis loss.

Because of these properties, pure iron is commonly used in magnetic cores, laboratory reference materials, and specialized electrical applications. However, pure iron lacks mechanical strength and corrosion resistance, which limits its use in structural components.

Cast iron (gray iron, ductile iron) and magnetism

Cast iron remains magnetic, but its behavior differs from pure iron. In gray iron, carbon appears as graphite flakes, which interrupt magnetic continuity and reduce permeability. Ductile iron performs slightly better magnetically because graphite forms spherical nodules instead of flakes.

From a manufacturing perspective, cast iron’s magnetism is often sufficient for magnetic separation and handling. However, it is less suitable for precision magnetic applications. Its heterogeneous structure also causes uneven residual magnetism after machining or heat exposure.

Wrought iron and low-carbon iron

Wrought iron and low-carbon iron exhibit stable and predictable magnetic behavior. Their low carbon content allows better domain alignment than high-carbon steels, while still offering improved ductility compared with pure iron.

Historically, wrought iron was widely used in magnetic and electrical applications before modern alloys became available. Today, low-carbon iron still appears in components where moderate strength and reliable magnetism are both required.

Differences between iron and iron-based alloys

Iron-based alloys modify magnetic behavior intentionally. Adding carbon, chromium, nickel, or manganese improves strength, corrosion resistance, or heat tolerance, but often weakens magnetism.

As alloy complexity increases, magnetic predictability decreases. This is why engineers cannot assume that “iron-based” automatically means “magnetic.” The exact composition and processing history determine the final behavior, not the base element alone.

Iron vs steel vs stainless steel (magnetic perspective)

Iron is consistently magnetic, but steel machining parts and stainless steel machining parts vary widely. Carbon steels are usually magnetic, while alloy steels show reduced or altered magnetism. Stainless steels differ even more: ferritic and martensitic grades are magnetic, while most austenitic grades are effectively non-magnetic.

This distinction matters in sourcing and inspection. Many procurement errors occur when buyers assume all steels behave like iron. In applications involving sensors, magnetic fixtures, or electromagnetic systems, material grade selection must account for these differences to avoid performance issues.

How to Permanently Magnetize Iron

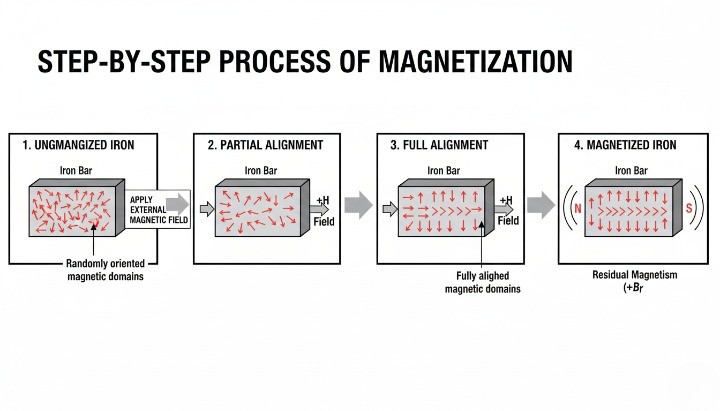

Magnetizing iron using an external magnetic field

Iron becomes magnetized when it is exposed to a sufficiently strong external magnetic field. This field forces many magnetic domains inside the iron to rotate and align in the same direction. Common methods include placing iron in contact with a permanent magnet, passing it through a magnetic coil, or exposing it to an electromagnet.

In industrial settings, magnetization often happens unintentionally. Magnetic chucks, lifting magnets, or inspection tools can leave iron parts partially magnetized. While this effect may seem minor, it can influence downstream machining, assembly, or measurement accuracy if not controlled.

Alignment of magnetic domains during magnetization

During magnetization, domain alignment follows a predictable pattern. Domains that already point close to the applied field direction grow larger, while poorly aligned domains shrink or rotate. As the field strength increases, more domains align, and the overall magnetic strength rises.

This process explains why magnetization is gradual rather than instantaneous. It also explains why reversing or removing the field does not fully restore the original state. Some domains remain partially aligned, creating residual magnetism that persists until actively removed through demagnetization.

Limits of permanent magnetization in iron

Iron has clear limits when it comes to permanent magnetization. While it magnetizes easily, it also demagnetizes easily. Once the external field is removed, thermal motion and internal stresses gradually randomize domain orientation.

This behavior makes iron unsuitable for applications requiring long-term magnetic stability. In practice, iron acts as a soft magnetic material, optimized for rapid magnetization and demagnetization rather than long-term retention. This limitation is a design feature in many electrical systems, not a flaw.

Why iron loses magnetism more easily than permanent magnet materials?

Iron loses magnetism easily because its atomic structure does not strongly lock domains in place. The energy barriers that prevent domain movement are relatively low, so vibration, heat, or mechanical shock can disrupt alignment.

Permanent magnet materials are engineered differently. They use alloying and crystal structures that resist domain rotation. Iron prioritizes responsiveness and permeability, while permanent magnets prioritize stability. Understanding this distinction prevents incorrect material selection in magnetic systems.

Iron vs true permanent magnets (NdFeB, Alnico)

Iron and permanent magnets serve different roles. Iron guides and amplifies magnetic fields, while permanent magnets generate and store them. Materials like neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) and Alnico contain alloy systems designed to maintain magnetization over long periods.

From an engineering perspective, iron complements permanent magnets rather than replacing them. Iron cores appear in motors and transformers, while permanent magnets provide the magnetic source. Confusing these roles often leads to unrealistic performance expectations or cost inefficiencies.

Factors Affecting Iron’s Magnetic Behavior

Temperature effects and Curie temperature

Temperature has the strongest influence on iron’s magnetism. As iron heats up, atomic vibrations disrupt domain alignment. At the Curie temperature (about 770 °C), iron loses ferromagnetism completely and becomes paramagnetic.

This effect matters in welding, heat treatment, and high-temperature service environments. Parts that experience thermal cycles may change magnetic behavior even if their shape and dimensions remain unchanged. Engineers must account for this when designing or inspecting heat-exposed components.

Mechanical stress, deformation, and cold working

Mechanical stress alters magnetic behavior by distorting the crystal lattice. Cold working processes such as bending, stamping, or aggressive machining introduce internal stresses that interfere with domain alignment.

As a result, cold-worked iron may show uneven or localized magnetism. This effect explains why some machined parts attract chips more strongly in specific areas. Stress-relief processes can reduce these inconsistencies, improving both magnetic and dimensional stability.

Heat treatment and phase changes

Heat treatment changes iron’s internal structure and directly affects magnetism. Annealing can reduce residual stresses and improve magnetic softness, while quenching and rapid cooling can introduce phases that reduce permeability.

Phase transformations alter how domains form and move. Even when the chemical composition stays the same, different thermal histories can produce very different magnetic responses. This is why magnetic behavior should be evaluated after final processing, not before.

Alloying elements and impurities

Alloying elements disrupt magnetic order to varying degrees. Carbon, chromium, manganese, and nickel all interfere with domain alignment. As alloy content increases, magnetism usually weakens and becomes less predictable.

Impurities have a similar effect. Non-metallic inclusions and uneven composition act as barriers to domain movement. For applications that rely on stable magnetic behavior, material specifications must tightly control both alloying levels and cleanliness.

Strength and duration of applied magnetic fields

The strength and duration of an applied magnetic field determine how deeply domains align. Weak fields produce limited, temporary effects. Strong or prolonged exposure leads to deeper alignment and higher residual magnetism.

In manufacturing environments, repeated exposure to magnetic fixtures or lifting systems can gradually increase magnetization. Without deliberate demagnetization steps, this buildup may interfere with automation, inspection sensors, or cleanliness requirements.

Engineering and Manufacturing Implications of Iron Magnetism

Iron’s magnetic behavior directly affects CNC machining parts efficiency and overall part quality. Magnetized workpieces attract chips, especially fine iron swarf, which can cling to cutting edges and finished surfaces. This buildup increases tool wear, affects surface finish, and complicates coolant flow.

Machinists often encounter inconsistent chip evacuation when residual magnetism varies across a part. To maintain stable machining conditions, many shops demagnetize iron components after roughing or before finishing. This step improves cleanliness, dimensional accuracy, and repeatability in precision machining operations.

Effects of magnetic chips and workholding

Magnetic chips create both advantages and risks. Magnetic conveyors and separators remove iron chips efficiently, improving shop safety and cleanliness. However, uncontrolled chip attraction can cause chips to embed into surfaces or fixtures during CNC turning parts production.

Magnetic workholding systems rely on iron’s permeability to provide strong clamping forces. While effective, they require careful setup. Uneven magnetization can distort thin parts or cause local stress. Engineers must balance holding force with part geometry to avoid deformation during machining.

Magnetism in die casting and secondary machining

In die casting, iron magnetism plays a smaller role during casting but becomes relevant during secondary operations. Custom die casting parts made from cast iron may retain localized magnetism after trimming, drilling, or milling.

This residual magnetism can interfere with automated handling systems or cause chips to cling during finishing. Manufacturers often include demagnetization steps after machining to stabilize downstream assembly and inspection. Ignoring this step increases the risk of contamination and inconsistent quality.

Magnetic influence on sensors, inspection, and automation

Magnetic fields can interfere with sensors used in automated inspection and assembly. Proximity sensors, Hall-effect devices, and vision systems may misread positions if parts carry residual magnetism, creating challenges for quality control processes in automated production lines.

In quality inspection, magnetized parts can attract metallic debris, affecting measurements. CMM probes and optical systems require clean, stable surfaces. Many production lines demagnetize iron components before inspection to ensure reliable data and reduce false rejections.

When magnetic behavior becomes a design or sourcing risk

Magnetic behavior becomes a risk when it is not specified or controlled. Designers may assume “iron-based” automatically means “acceptable,” while suppliers deliver parts with unexpected magnetism due to processing differences.

This mismatch creates disputes during incoming inspection and assembly. To reduce risk, engineers should define magnetic requirements clearly, especially for parts used near sensors, electronics, or automated systems. When projects involve magnetic-sensitive components or tight production tolerances, it is often more efficient to contact an engineering team for a manufacturing review before releasing the RFQ.

Common Uses of Magnetic Iron

Electric motors, transformers, and electromagnets

Iron plays a central role in electrical systems. Iron cores concentrate magnetic flux, improving efficiency in motors and transformers. High permeability allows strong magnetic fields with minimal energy loss.

In electromagnets, iron amplifies the magnetic field generated by electric current. This combination enables lifting magnets, relays, and solenoids used across industrial automation and material handling.

Magnetic cores and shielding applications

Iron is widely used in magnetic cores and shielding because it redirects magnetic fields effectively. Magnetic shielding protects sensitive electronics from external interference by guiding fields away from critical components.

In power electronics and communication systems, iron-based shielding improves signal stability. Engineers select iron grades carefully to balance permeability, saturation limits, and thermal performance.

Industrial machinery and automation systems

Automation systems rely on iron’s predictable magnetism. Magnetic clamps, conveyors, and separators depend on iron components to function reliably.

In robotic systems, iron’s interaction with magnetic sensors must remain consistent. Variations in magnetism can disrupt positioning or detection. Controlled material selection and post-processing help maintain stable automation performance.

Manufacturing, sorting, and material identification

Magnetic separation is one of the most efficient methods for material sorting. Iron’s strong response allows fast separation from non-magnetic metals such as aluminum or copper.

Recycling facilities, foundries, and machining shops use magnetic systems to identify and segregate iron-based materials. This capability reduces contamination and improves material recovery rates.

Quality inspection and non-destructive testing

Iron’s magnetic properties enable several non-destructive testing methods. Magnetic particle inspection (MPI) uses iron magnetism to reveal surface and near-surface defects.

These techniques support quality assurance in critical components such as castings, forgings, and machined parts. Proper control of magnetization and demagnetization ensures accurate inspection results without introducing downstream issues.

Frequently Asked Questions About Iron Magnetism

Is iron always magnetic?

No. Iron is magnetic under normal conditions, but high temperature, alloying, or specific heat treatments can reduce or eliminate its magnetism. Above its Curie temperature, iron loses ferromagnetism completely.

Is iron more magnetic than steel?

Pure iron is generally more magnetically responsive than most steels. Steel’s magnetic behavior depends on carbon content and alloying elements. Some steels remain strongly magnetic, while others show reduced or negligible magnetism.

Does rust affect iron’s magnetism?

Rust itself is weakly magnetic and can slightly reduce overall magnetic response. However, rust mainly affects surface condition rather than core magnetism. Severe corrosion can disrupt magnetic continuity and measurement reliability.

Can machining or heat treatment change iron’s magnetic behavior?

Yes. Machining introduces stress, and heat treatment alters internal structure. Both processes can change domain alignment, creating or reducing residual magnetism. Final magnetic behavior should always be evaluated after processing.

Is iron the only magnetic metal?

No. Iron, cobalt, and nickel are the primary ferromagnetic metals. Iron is the most widely used due to its availability, cost, and versatility in engineering and manufacturing applications.