Stainless steel can rust. It resists rust, but it is not rust-proof. If you have seen orange spots on “stainless,” you already know the confusion.

Here is why this topic matters in real projects. Buyers often specify “stainless” and assume corrosion risk disappears. Then parts sit outdoors, see salt, trap moisture, or pick up shop contamination. A small surface issue turns into rework, rejects, or a supplier dispute.

In this guide, you will learn what makes stainless resist rust, what conditions defeat it, and how to choose grades and specs that hold up. You will also get practical manufacturing and RFQ rules that reduce corrosion risk before production.

Does Stainless Steel Rust?

Yes—stainless steel can rust, especially in chloride-rich, low-oxygen, or contaminated conditions. However, it usually does not rust the same way carbon steel does, and many “rust” cases are preventable when material choice and processing are handled correctly, including stainless steel machining parts produced with controlled surface integrity.

Stainless earns its reputation because it forms a thin, protective surface film. That film can repair itself when oxygen is present, but it can also break down when the environment overwhelms the alloy grade or the surface condition. Stainless corrosion often starts locally, so small spots matter more than they look.

Stainless steel is rust-resistant, not rust-proof

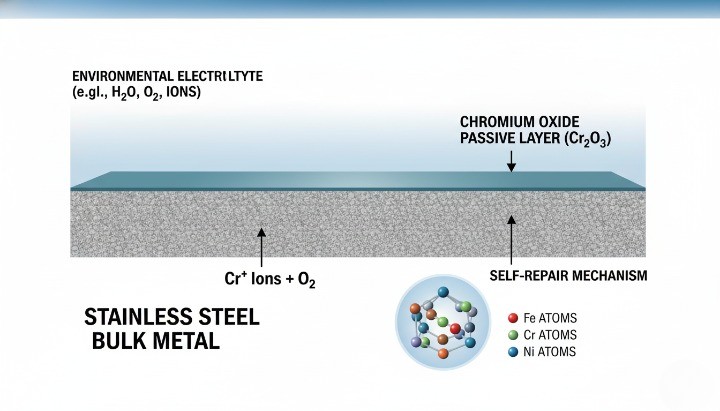

Stainless steel resists uniform rusting because it passivates. Passivation means the surface forms a stable oxide layer that blocks further attack.

Carbon steel rust creates a porous layer that flakes and exposes fresh metal. Stainless behaves differently because its passive film slows oxygen diffusion and protects the base metal. That difference drives the “stainless” name, but the protection still has limits.

Common misconceptions about “stainless” steel

Procurement teams often see these assumptions in RFQs and internal discussions:

-

“Stainless won’t rust outdoors.”

-

“304 and 316 are basically the same.”

-

“If it rusts, the supplier used fake material.”

-

“A quick polish fixes everything.”

In practice, stainless performance depends on grade + environment + surface condition + design details. When one of these goes wrong, corrosion can appear even on genuine stainless.

Why Stainless Steel Resists Rust?

Stainless resists rust because chromium in the alloy forms a self-healing passive film on the surface. That film can rebuild after light damage if oxygen is available, which explains why stainless steel material selection is fundamental to corrosion performance.

The real value for engineering is simple: stainless can protect itself without paint, as long as the alloy and the operating conditions support stable passivation. That is why stainless performs well in many wet, industrial, and hygienic environments. (source:)

Chromium content and the passive oxide layer

Chromium is the core element. When chromium-bearing steel meets oxygen (air or dissolved oxygen in water), it forms a microscopically thin chromium oxide layer. This layer blocks corrosion from spreading into the bulk metal, and it can repair itself after minor scratching.

Many references describe stainless as requiring at least about 10.5% chromium to sustain passivation in typical conditions.

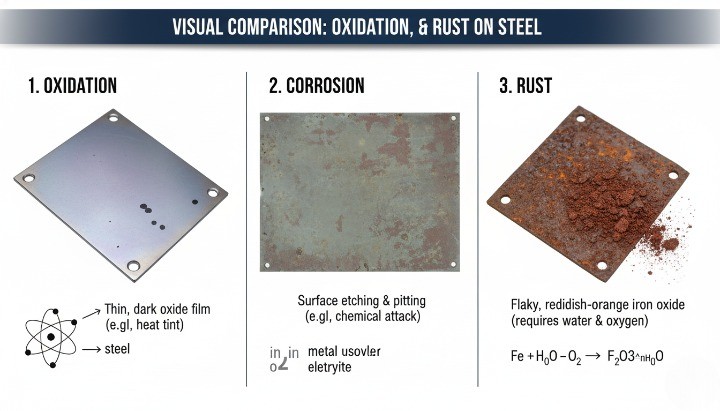

Oxidation vs rust vs corrosion

Teams mix these terms, so it helps to separate them:

-

Oxidation: a broad chemical reaction with oxygen. Many metals oxidize.

-

Corrosion: the broader process of metal degradation via chemical or electrochemical reactions.

-

Rust: iron oxides/hydroxides associated with iron-based alloys, often seen as orange/brown products.

Stainless can oxidize and corrode, but it often does so in localized forms (pitting, crevice attack) rather than uniform rusting. That is why you may see small orange spots while the rest of the surface looks fine.

Why Stainless Steel Can Still Rust?

Stainless rusts when the passive film cannot form, cannot repair, or cannot survive the environment. Chlorides, trapped moisture, low oxygen, and surface contamination are the most common triggers.

Many failures look like “rust,” but the mechanism can differ. Localized corrosion can create pits that grow under deposits, gaskets, or stagnant water. Those pits can compromise sealing and fatigue life, even when surface discoloration looks minor.

Chlorides, salt water, and aggressive environments

Chlorides are the number-one driver of stainless corrosion in real installations. Salt spray, seawater, coastal air, de-icing salts, and many process fluids contain chlorides.

Chlorides attack the passive film and promote pit initiation. Some grades handle chlorides far better than others, which is why “stainless” alone is not a safe specification in marine or salted-road environments.

Crevice corrosion and stagnant moisture

Crevice corrosion forms in tight gaps where water sits and oxygen cannot circulate. Think of:

-

Under gaskets and washers

-

Lap joints and overlapping plates

-

Thread roots and poorly drained interfaces

-

Deposits, scale, and trapped dirt

In crevices, the chemistry shifts and the passive film struggles to repair. The outside surface may look fine while corrosion grows inside the gap.

Pitting corrosion and localized attack

Pitting is a localized form that creates small holes that can grow deep. It often starts under deposits or in chloride exposure.

From a reliability standpoint, pitting matters because it concentrates stress. A tiny pit can drive premature cracking under cyclic loads, even when overall mass loss is small. When sealing or hygiene matters, pitting also creates hard-to-clean sites.

Engineers often use comparative metrics like CPT/CCT behavior or pitting/crevice resistance rankings to evaluate suitability in chlorides. In chloride-bearing solutions, common grades like 304L can rank lower than higher-alloy options.

Damage or breakdown of the passive layer

The passive film is thin, so surface condition matters. These factors can weaken passivation:

-

Abrasive wear or repeated scratching

-

Heat tint from welding without proper cleanup

-

Acid residues or cleaning chemicals left to dry

-

Scale from high-temperature operations

-

Poor drainage that keeps the surface wet with low oxygen

The key detail: stainless often recovers if oxygen returns and the surface is clean. It struggles when deposits, chlorides, and stagnant water persist.

Carbon steel contamination during machining or fabrication

This is one of the most under-specified causes in B2B supply chains. Free iron contamination can create rust spots on stainless even when the stainless itself remains corrosion-resistant, which is why consistent quality control during machining and handling is critical for stainless steel components.

Common contamination sources include:

-

Grinding dust from carbon steel near stainless parts

-

Shared wire brushes, sanding belts, or blasting media

-

Steel pallets, steel shot, or handling damage

-

Embedded particles from cutting or deburring tools

If you see “surface rust” shortly after delivery, contamination is often the first thing to investigate. Passivation practices often aim to remove free iron and restore a clean passive surface.

Does Stainless Steel Rust in Water or Outdoors?

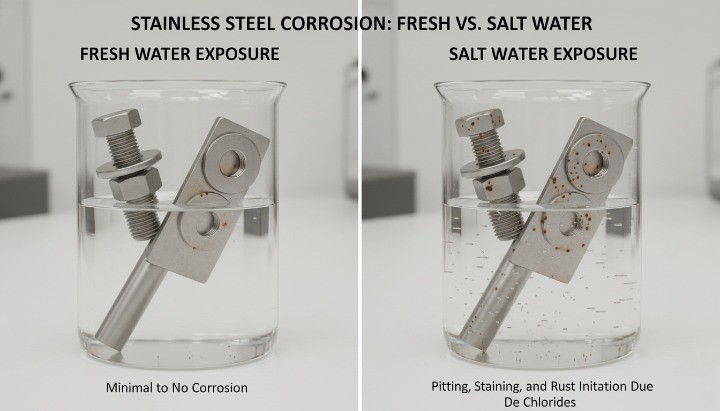

Stainless can rust in water or outdoors, but risk depends on chloride level, oxygen access, and drying behavior. Fresh water and dry cycles usually reduce risk. Salt exposure and trapped moisture raise it, which is why stainless rail fittings used in outdoor assemblies require careful grade selection and surface control.

When teams ask “Will stainless rust in water?” they usually mean “Can I use it outdoors with rain, washing, or occasional wetting?” Your answer should focus on the environment and the grade, not the label “stainless.”

Fresh water vs salt water exposure

Fresh water systems with good oxygen and low chlorides often allow stainless to maintain passivation. Salt water and chloride-bearing fluids push stainless toward pitting and crevice attack, especially on common austenitic grades.

If your application includes salt spray, seawater splash, or brine, treat it as a corrosion design problem, not a cosmetic issue. Specify grade, finish, and design rules up front.

Outdoor, coastal, and industrial environments

Outdoor stainless can perform well, but environment decides the outcome:

-

Urban/industrial air can include pollutants that keep surfaces wet and aggressive.

-

Coastal zones add salt deposition that concentrates as water evaporates.

-

Heavily salted roads expose hardware to chloride cycles and crevice traps.

If you cannot guarantee routine cleaning, better drainage, and minimal crevices, move up in grade and tighten your surface and passivation requirements.

Do Different Stainless Steel Grades Rust?

Yes. Different grades show very different corrosion resistance, especially in chlorides. In practice, grade choice often decides whether you see staining in months or stable performance for years.

Most sourcing issues come from “generic stainless” specifications. If you specify 304 for a coastal bracket, you may get real 304 and still see corrosion. Better specs reduce blame games and protect total cost.

Will 304 stainless steel rust?

304 can rust, especially outdoors near the sea or where de-icing salts exist. 304 performs well in many indoor and mild outdoor environments, but it lacks the chloride resistance that higher-alloy grades provide.

If the part faces frequent wetting and slow drying, or if it includes crevices, 304 becomes more vulnerable to localized corrosion.

304 vs 316 stainless steel corrosion resistance

316 typically resists pitting and crevice corrosion better than 304 in chloride environments because it contains molybdenum, which is why 316 stainless steel manifolds used in chloride-prone systems are often specified for marine, coastal, or salt-exposed applications. 304 and 316 also differ in common composition ranges, and many engineering guides highlight that 316 includes about 2% molybdenum.

Here is a practical comparison you can use in sourcing discussions:

| Topic | 304 Stainless Steel | 316 Stainless Steel |

|---|---|---|

| Best fit | General-purpose indoor/mild outdoor | Chloride exposure, coastal, more aggressive service |

| Chloride pitting/crevice resistance | Lower | Higher due to Mo addition () |

| Typical use examples | Enclosures, indoor equipment, mild washdown | Marine hardware, coastal fixtures, salty washdown |

| Cost direction | Lower | Higher |

This table does not mean 316 never corrodes. It means 316 gives you more margin when chlorides and crevices exist.

Choosing the right grade for the application

Use a simple decision rule:

-

If you can keep the surface clean, drained, and low-chloride, 304 often works.

-

If chlorides, salt spray, or crevices exist, 316 is often the safer baseline.

-

If you face severe chlorides or high temperature chloride service, you may need higher-alloy options beyond 316.

You do not need to over-specify every part. Instead, match grade to exposure and failure consequence.

Manufacturing and Fabrication Factors That Increase Rust Risk

Manufacturing choices can increase rust risk even when you choose the correct grade. Surface integrity, welding cleanup, and passivation practices often decide whether stainless stays clean in service.

Competitor articles often say “design, fabrication, maintenance,” but they rarely translate that into supplier-ready requirements. This section does exactly that.

Machining effects on surface integrity

Machining can help or hurt corrosion resistance. Well-controlled CNC machining parts produce a clean surface and consistent finish, which supports stable passivation over time. Poor practices, however, can create:

-

Embedded contamination from tools or nearby carbon steel operations

-

Smearing and roughness that traps moisture and chloride deposits

-

Burrs and sharp edges that become crevice initiators

-

Local overheating that alters the surface condition

If you want corrosion resistance, you should treat surface finish as functional, not cosmetic. Specify the finish requirement on corrosion-critical areas, and ask the supplier how they control cross-contamination in the shop.

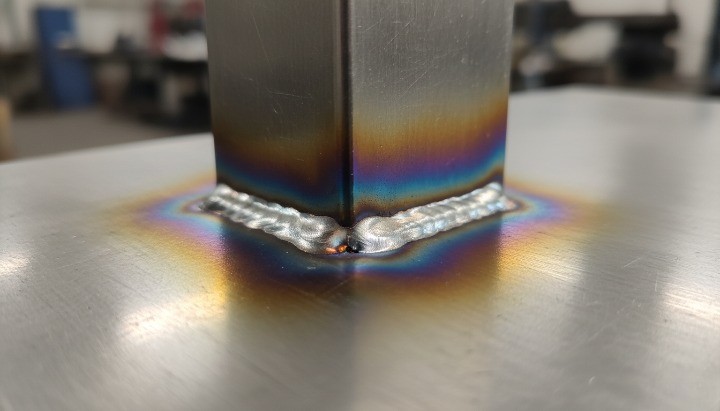

Welding quality and heat-affected zones

Welding introduces heat tint and oxide scale. If you do not remove or treat these areas, you can reduce corrosion resistance near the weld, even on good alloy.

Practical control points include:

-

Correct filler selection for the base alloy and environment

-

Controlled heat input to limit sensitization risk in some cases

-

Post-weld cleaning (mechanical + chemical as needed)

-

Avoiding crevices and poor drainage around weld geometry

If your assembly must survive chlorides, you should not accept “as-welded with discoloration” as a default.

Surface finish, passivation, and post-processing

Passivation is not marketing language. It is a defined industrial practice that aims to clean stainless surfaces and remove free iron contamination, which improves corrosion performance and is often implemented as part of controlled surface treatment processes for stainless steel parts.

ASTM A967 covers chemical passivation treatments for stainless steel parts and includes guidance on cleaning and testing to confirm effectiveness. The British Stainless Steel Association also discusses passivation approaches and references ASTM A967 treatments.

When you source stainless parts, you can request passivation to a recognized standard and require validation tests when the application justifies it. That request often prevents “mystery rust” on new parts.

How to Prevent Stainless Steel from Rusting?

You prevent stainless rust by controlling grade, design details, and surface condition. Maintenance matters, but the biggest wins happen before the part ships, especially in sealing interfaces where stainless O-ring components help eliminate crevices that trap moisture and chlorides.

I recommend you treat corrosion prevention like a chain. If one link fails, the system fails. Grade alone does not save a part with crevices and chloride deposits. Great design also struggles if a supplier contaminates the surface with free iron.

Material and grade selection

Start with exposure. Ask these questions:

-

Will the part see chlorides (salt spray, brine, de-icing salts, chloride cleaners)?

-

Will it stay wet or dry quickly?

-

Can you clean it routinely, or will it sit with deposits?

Then choose a grade that gives margin. If chlorides and crevices exist, do not default to “304.” Use 316 as a baseline and evaluate higher alloys when severity rises.

Design practices to reduce corrosion risk

Good corrosion design often looks “boring,” but it saves money:

-

Avoid tight crevices and lap joints where water sits

-

Add drainage paths and avoid trapped pockets

-

Use continuous welds where gaps would trap moisture

-

Select fasteners and washers that match corrosion resistance

-

Keep dissimilar metals in mind when the environment is conductive

These moves reduce localized corrosion drivers before they start.

Fabrication, handling, and surface treatment best practices

Ask your supplier about these controls:

-

Separate tools and abrasives for stainless vs carbon steel

-

Controlled cleaning steps before final packing

-

Passivation requirement for corrosion-critical parts (as needed)

-

Protection during shipping to prevent iron dust exposure

-

Packaging that avoids metal-to-metal abrasion

If you do not specify these details, suppliers may optimize for speed and cost. That approach often increases corrosion complaints later.

How Buyers and Engineers Should Specify Stainless Steel

A good stainless specification prevents RFQ ambiguity and reduces corrosion disputes. You want suppliers to quote the same intent, not guess your risk tolerance, which is why aligning technical details early—and knowing when to contact suppliers for a process-aligned quote—matters more than many teams expect.

When I review stainless RFQs, I usually see one of two problems: the RFQ says only “stainless steel,” or it specifies a grade but ignores environment, finish, and post-processing. Both lead to inconsistent outcomes.

Environmental exposure and service conditions

Add a short exposure statement in the RFQ and drawing notes. Include:

-

Indoor vs outdoor, coastal distance if relevant

-

Presence of salt spray, de-icing salts, or chloride cleaners

-

Wet/dry cycle behavior (continuous wet vs intermittent wash)

-

Temperature range if it affects chemistry

-

“No stagnant water allowed” if drainage matters

This one paragraph often improves supplier alignment more than pages of generic language.

Surface finish and inspection requirements

If corrosion performance matters, specify surface requirements in a controlled way:

-

Surface finish target on exposed or sealing surfaces

-

No embedded contamination and controlled handling

-

Passivation requirement when justified (reference ASTM A967)

-

Visual acceptance criteria (staining limits, weld discoloration limits)

You do not need to over-inspect everything. Instead, tie inspection to function and exposure. That approach controls cost.

Avoiding corrosion-related issues in RFQs

Use these RFQ safeguards:

-

Define the exact grade (for example: 304/304L or 316/316L)

-

Define post-processing if needed (passivation standard reference)

-

Define surface finish zones (critical vs non-critical)

-

Require suppliers to state assumptions in the quote

-

Ask for evidence of contamination control (tool separation, cleaning steps)

Key Takeaways

Stainless steel can rust under specific conditions, especially with chlorides, crevices, stagnant moisture, or surface contamination. Stainless resists rust because chromium enables passivation, but the passive film has limits and depends on oxygen access and clean surfaces.

Proper grade selection and manufacturing control reduce long-term risk. Choose grades based on exposure (304 vs 316 is not a cosmetic decision), design out crevices, and specify surface handling and passivation when the application justifies it. If you want fewer corrosion surprises, build corrosion intent into your RFQ and supplier process from the start.

If you are sourcing stainless CNC parts or assemblies and you want a quote aligned with real corrosion risk, share your environment, service conditions, and critical surfaces. HM, as a professional CNC machining and manufacturing partner, can review your design intent, recommend practical specifications, and support machining, finishing, and inspection for stable production outcomes.