the exact temperature at which copper begins to melt.

Many engineers and buyers search this topic because real projects fail when the melting point is treated as a simple textbook number. Copper often softens, oxidizes, or deforms long before it fully melts. These behaviors affect machining stability, joining quality, and casting feasibility, especially when purity, alloys, or heating conditions change.

In this article, you will get the accurate melting temperature of copper, understand how it behaves before melting, and learn how to apply this data correctly in material selection and manufacturing decisions. If you need a broader reference on metal properties and processing considerations, you can also review HM’s material capabilities and engineering guidance:

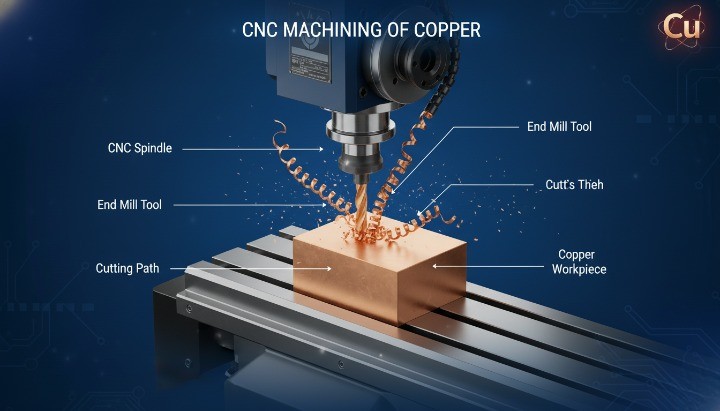

Copper melts at 1084.62 °C (1984 °F, 1357.77 K). This temperature marks the point where solid copper begins to transition into a liquid phase under standard atmospheric pressure. For most engineering references, this value applies to pure copper and serves as the baseline for material selection, thermal calculations, and process planning in precision CNC machining of metal parts

In practice, engineers should treat this number as a reference point, not an operating target. Real manufacturing outcomes depend on purity, heating rate, atmosphere, and whether copper is used in pure or alloyed form. Understanding what this temperature truly represents helps prevent deformation, surface damage, and process instability.

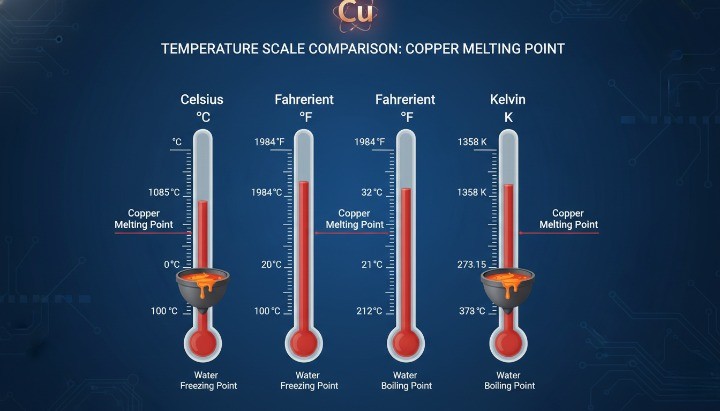

Copper Melting Point in Celsius, Fahrenheit, and Kelvin

The melting point of copper is well established and consistently reported across authoritative material databases.

-

1084.62 °C (degrees Celsius)

-

1984 °F (degrees Fahrenheit)

-

1357.77 K (Kelvin)

Most industrial standards, material handbooks, and academic references agree on these values, including data published by NIST and widely cited metallurgy sources. Engineers typically work in Celsius, while procurement teams and global documentation may reference Fahrenheit or Kelvin depending on region and application.

This temperature applies to pure copper at normal pressure. Once alloying elements or impurities enter the material, the melting behavior changes and often shifts from a single temperature to a melting range.

Melting Point vs Softening Temperature of Copper

Copper does not remain rigid until it suddenly melts. It begins to soften at temperatures far below its melting point, which is a critical distinction many teams overlook.

As temperature rises:

-

Copper loses mechanical strength well before 1084 °C

-

Elastic modulus and yield strength drop rapidly

-

Dimensional stability decreases during heating

For manufacturing, this means:

-

Copper parts can distort during heating without melting

-

Fixtures and supports matter long before liquid formation

-

Machining accuracy and flatness can suffer after thermal exposure

The melting point defines phase change, not usable strength. Engineers who plan processes based only on the melting point often underestimate deformation risk. Correct decisions require understanding both softening behavior and final melting temperature, especially in CNC machining, joining, and thermal treatments.

Why Copper Has a Relatively High Melting Point?

Copper has a relatively high melting point because its atomic structure forms strong metallic bonds. These bonds require more thermal energy to break compared with many common engineering metals. As a result, copper stays solid at temperatures where aluminum already melts, yet it still melts earlier than most steels. This balance explains copper’s wide use in electrical, thermal, and industrial applications that involve heat exposure.

From a manufacturing perspective, this melting behavior affects energy consumption, process windows, tooling life, and deformation risk. Engineers who understand why copper melts where it does can predict performance more accurately and avoid costly trial-and-error.

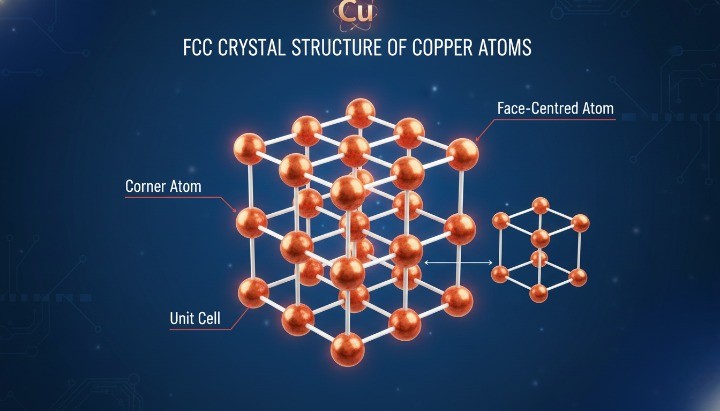

Atomic Structure and Metallic Bonding of Copper

Copper atoms arrange themselves in a face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal structure, which promotes dense atomic packing and strong metallic bonding. Each copper atom shares free electrons with neighboring atoms, creating a stable and cohesive lattice.

Key reasons copper resists melting:

-

High electron mobility strengthens metallic bonds

-

Dense FCC packing increases atomic cohesion

-

Strong bond energy requires more heat to disrupt

This structure also explains copper’s excellent electrical and thermal conductivity. However, the same bonding strength that improves conductivity also raises the energy threshold required for melting, compared with lighter metals.

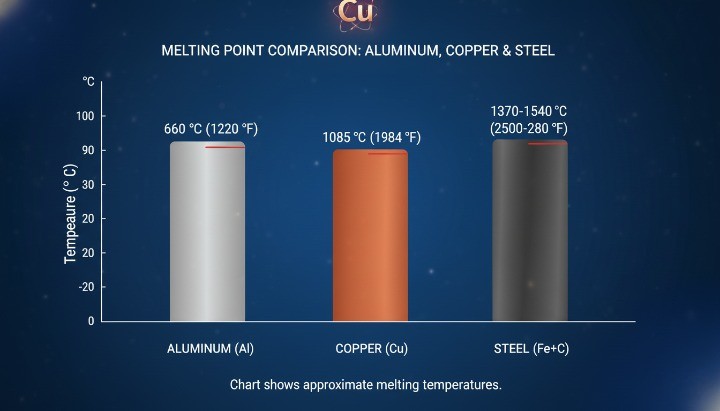

Copper vs Aluminum and Steel: Melting Point Comparison

Comparing melting points across common metals helps explain material selection decisions in machining and casting.

| Metal | Approx. Melting Point (°C) | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | ~660 °C | Easy to melt, ideal for die casting |

| Copper | 1084.62 °C | High thermal stability, harder to cast |

| Carbon steel | ~1370 °C | Very high heat resistance, energy intensive |

This comparison highlights several practical realities:

-

Aluminum melts easily, enabling high-pressure die casting

-

Copper needs significantly more energy to melt

-

Steel resists melting even more, limiting casting options

Copper sits in the middle. It offers better heat resistance than aluminum but demands more careful thermal control during processing. This is one reason copper appears far less often in die casting and far more in CNC machining or post-cast finishing workflows.

Suggested image placement: [Image: Bar chart comparing melting points of aluminum, copper, and steel] Alt text: Melting point comparison of aluminum, copper, and steel for manufacturing reference

At What Temperature Does Copper Melt in Real Manufacturing Conditions?

In real manufacturing, copper rarely melts at a single, perfectly fixed temperature. While pure copper begins to melt at 1084.62 °C, actual production conditions introduce variables such as purity, alloying, heating speed, and atmosphere. These factors shift copper’s melting behavior and often create a melting range instead of a sharp melting point.

For engineers and buyers, this distinction matters. Quoting the textbook melting point without considering material grade or process conditions often leads to warped parts, surface oxidation, or failed trials during heating, joining, or casting.

Pure Copper vs Commercial Copper Grades

Pure copper defines the reference melting point, but most industrial copper is not 100% pure. Even small amounts of oxygen or trace elements change how copper behaves under heat, which directly affects industrial manufacturing processes for copper components

Common commercial copper grades include:

-

Oxygen-Free Copper (OFC / C10100) – very high purity, closest to theoretical melting point

-

Electrolytic Tough Pitch (ETP / C11000) – contains oxygen, slightly altered melting behavior

-

Deoxidized Copper (C12200) – improved weldability, minor melting range shift

Key manufacturing implications:

-

Higher purity copper melts closer to the theoretical value

-

Oxygen-bearing copper oxidizes more easily during heating

-

Commercial grades may soften earlier, even if melting starts near 1084 °C

Engineers should specify copper grade explicitly when planning thermal processes. “Copper” alone is not precise enough for reliable process control.

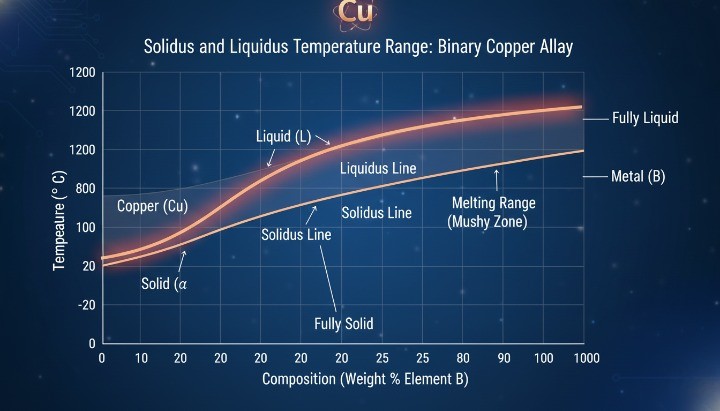

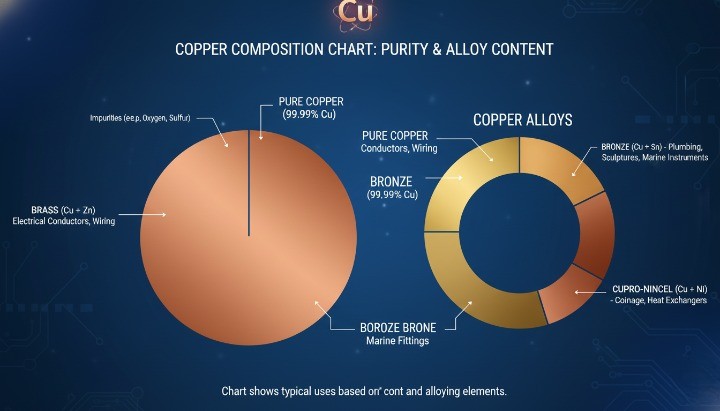

Copper vs Copper Alloys: Melting Range Differences

Copper alloys behave very differently from pure copper. Most copper alloys do not melt at a single temperature. Instead, they soften and melt across a temperature range defined by their composition, which is especially important when dealing with bronze alloys commonly produced through precision CNC machining

Typical examples:

-

Brass (Cu–Zn): lower melting range than pure copper

-

Bronze (Cu–Sn): wider melting range, improved castability

-

Cu–Ni alloys: higher thermal stability, elevated melting behavior

Practical consequences in manufacturing:

-

Alloys may start melting hundreds of degrees before full liquefaction

-

Partial melting can cause surface collapse or internal defects

-

Process windows become narrower and harder to control

For casting and joining, engineers must design around:

-

Solidus temperature (where melting begins)

-

Liquidus temperature (where material becomes fully liquid)

Treating copper alloys as if they melt like pure copper is a common and costly mistake.

Factors That Affect Copper’s Melting Behavior

Copper’s melting behavior depends on more than temperature alone. Several controllable and uncontrollable factors influence when copper softens, begins to melt, and flows. Ignoring these variables leads to inconsistent results, even when teams heat copper to the “correct” melting point. Understanding these factors helps engineers tighten process windows and avoid distortion, oxidation, or partial melting.

Purity and Alloying Elements

Material composition plays the largest role in how copper melts. Higher purity copper behaves more predictably, while alloying elements shift both the melting point and the melting range.

Key effects include:

-

Trace impurities lower the solidus temperature

-

Alloying elements widen the melting range

-

Oxygen content increases oxidation risk

For example:

-

Oxygen-free copper stays closer to the theoretical melting point

-

Brass and bronze begin melting earlier due to zinc or tin content

Always confirm chemical composition before thermal processing. Material certificates matter as much as temperature settings.

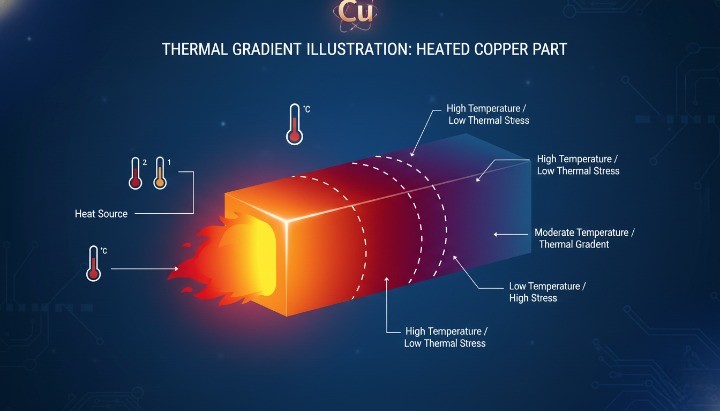

Heating Rate and Thermal Distribution

Copper conducts heat extremely well, but that strength can become a weakness. Uneven heating causes local softening or melting before the bulk material reaches target temperature.

Common risks include:

-

Hot spots near heat sources

-

Thermal gradients across thick sections

-

Early distortion without full melting

Rapid heating increases these risks, especially in:

-

Thick copper components

-

Complex geometries

-

Assemblies with mixed materials

Controlled heating improves outcomes by:

-

Reducing internal thermal stress

-

Maintaining dimensional stability

-

Preventing partial surface melting

Uniform heat distribution matters as much as peak temperature.

Atmospheric Conditions and Oxidation

Copper reacts quickly with oxygen at elevated temperatures. Oxidation does not change the melting point, but it changes how copper melts and flows, especially when surface condition and post-heating treatment are not properly controlled

At high temperatures:

-

Oxide layers form rapidly on exposed surfaces

-

Oxides reduce wetting and flow

-

Surface quality degrades during melting

Manufacturers often control atmosphere using:

-

Protective gases

-

Fluxes

-

Controlled furnace environments

Without atmosphere control:

-

Copper surfaces become brittle

-

Joining quality decreases

-

Casting defects increase

Managing oxidation is essential for predictable melting behavior, especially in joining and casting operations.

Copper Melting Point Compared with Other Metals

Copper melts at a higher temperature than aluminum, but at a lower temperature than most steels. This comparison helps you choose materials and processes with fewer surprises, especially when evaluating copper-based alloys such as brass components used in industrial applications. When you understand the gap between melting temperatures, you can predict energy needs, tooling limits, and distortion risk more accurately.

Engineers often use melting point comparisons to answer practical questions. Can we die cast it? Can we braze it safely? Will it lose strength during a heat cycle? The table below gives you a fast reference for common metals used in manufacturing.

Copper vs Aluminum

Aluminum melts much earlier than copper, which makes aluminum easier to cast and cheaper to melt. Most high-pressure die casting lines rely on aluminum (and zinc) because they can run at lower temperatures and protect die life. Copper’s higher melting temperature pushes energy use up and tightens the process window.

Here is the practical comparison most sourcing teams use:

| Topic | Aluminum | Copper |

|---|---|---|

| Melting point | ~660 °C | 1084.62 °C |

| Typical high-pressure die casting use | Very common | Rare |

| Energy to melt (relative) | Lower | Higher |

| Thermal conductivity | High | Very high |

| Common approach for tight tolerances | Cast + machine | Machine or cast + machine |

Aluminum also gives you more options for high-volume shapes. Copper usually fits better when you need conductivity, heat transfer, or wear behavior that aluminum cannot match.

Copper vs Steel and Stainless Steel

Most steels melt at higher temperatures than copper, but steel does not always outperform copper in heat-exposed applications. Steel retains strength better at moderate temperatures, while copper conducts heat quickly and spreads thermal load. Each material creates different design and manufacturing trade-offs.

Use this quick reference when you compare feasibility:

| Metal family | Typical melting range (°C) | What it means in manufacturing |

|---|---|---|

| Copper | 1084.62 °C | Higher heat than aluminum, careful oxidation control |

| Carbon steel | ~1370–1540 °C | High thermal margin, energy intensive to melt |

| Stainless steel | ~1400–1450 °C | High thermal margin, sensitive to overheating and oxidation |

If you plan a casting route, steel’s melting temperature usually rules out simple shop melting methods. Copper still demands serious thermal control, but it stays more accessible than steel for certain foundry setups.

How Copper Is Melted in Industrial Manufacturing?

Industrial copper melting focuses on control, not just temperature. Because copper melts at a relatively high temperature and oxidizes easily, manufacturers choose melting methods that deliver stable heat input, clean metal, and predictable flow. The right method depends on part size, alloy type, quality requirements, and downstream processes such as machining or joining.

Induction Melting of Copper

Induction melting is the preferred method for copper and copper alloys in modern manufacturing. It uses electromagnetic fields to heat the metal directly, which delivers fast response and precise temperature control. This approach suits copper because it limits contamination and improves consistency.

Key advantages include:

-

Rapid and uniform heating

-

Accurate temperature control

-

Lower oxidation compared to open-flame heating

-

Clean melt suitable for high-quality parts

Manufacturers commonly use induction melting for:

-

Copper alloy preparation

-

Precision casting pre-melts

-

Controlled joining and brazing operations

Induction systems also scale well. Small batches and larger production runs can use the same core technology with different power levels.

Crucible and Furnace Melting

Crucible and furnace melting remain common for copper in foundry and workshop environments. These methods rely on external heat sources to raise copper above its melting point. They work well for simpler setups but demand stricter process discipline.

Typical setups include:

-

Gas-fired furnaces

-

Electric resistance furnaces

-

Graphite or ceramic crucibles

Key considerations when melting copper this way:

-

Slower heating rates increase oxidation risk

-

Temperature overshoot happens easily

-

Slag and oxide removal becomes critical

These methods often suit:

-

Lower-volume production

-

Experimental or prototyping work

-

Alloy preparation before secondary processing

Careful atmosphere control and temperature monitoring are essential to avoid surface contamination and inconsistent flow.

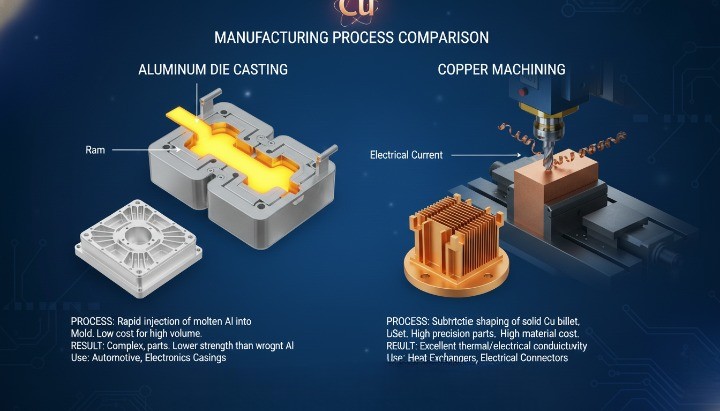

Why Copper Is Rarely Used in High-Pressure Die Casting?

High-pressure die casting rarely uses copper because its melting temperature shortens die life and narrows the process window. Die casting relies on rapid cycles, stable molds, and controlled solidification. Copper challenges all three.

Primary reasons include:

-

High melting temperature increases thermal stress on dies

-

Copper’s heat conductivity accelerates die wear

-

Oxidation and flow control become harder at high temperatures

As a result:

-

Aluminum and zinc dominate die casting applications

-

Copper appears mainly as an alloying element, not a base metal

-

Copper parts usually rely on CNC machining or hybrid routes

When copper geometry resembles a cast part, manufacturers often choose:

-

Near-net-shape casting with post-machining

-

Full CNC machining from solid stock

What Copper’s Melting Point Means for CNC Machining and Casting?

Copper’s melting point shapes how manufacturers choose between machining and casting. Although copper melts at a high temperature, many production challenges appear long before melting begins. Softening, heat buildup, and surface instability affect accuracy and repeatability. For this reason, engineers often base process decisions on thermal behavior during cutting and forming, not on melting temperature alone.

Understanding this relationship helps buyers avoid process routes that look economical on paper but fail in production.

Copper Melting Point and Machinability

Copper’s high melting point does not mean it machines easily. In fact, copper’s thermal properties create several machining challenges that require experience and control.

Key machinability characteristics include:

-

Extremely high thermal conductivity

-

Rapid heat transfer from cutting zone to tool

-

Tendency to smear rather than fracture

These properties lead to practical issues:

-

Cutting heat moves into the tool instead of the chip

-

Tool edges wear faster if parameters are wrong

-

Surface finish degrades when heat softens the workpiece

To machine copper successfully, manufacturers rely on:

-

Sharp tooling with optimized geometries

-

Controlled cutting speeds and feeds

-

Effective chip evacuation and coolant strategy

Copper rarely fails by melting during machining. Instead, it fails by softening, smearing, or losing dimensional stability under cutting loads. This is why experienced CNC shops treat copper as a thermal management problem, not a melting problem.

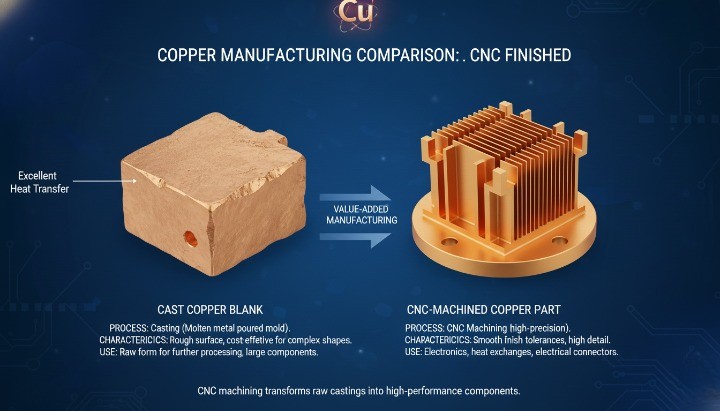

When CNC Machining Is Preferred Over Casting for Copper Parts?

CNC machining is often the preferred route for copper parts that demand accuracy, consistency, and clean surfaces. Casting copper requires higher temperatures, tighter atmosphere control, and careful solidification management. These demands raise cost and risk for many geometries.

CNC machining becomes the better choice when:

-

Tight tolerances matter

-

Surface finish affects performance

-

Internal features require precision

-

Production volumes stay low to medium

Casting copper may still make sense when:

-

Geometry is simple and thick

-

Electrical or thermal mass dominates design

-

Post-machining is planned for critical features

Many manufacturers choose a hybrid approach:

-

Near-net-shape copper casting

-

CNC finishing on critical surfaces

For most precision copper components, machining delivers better predictability than casting. This reality explains why copper parts in electronics, thermal systems, and industrial equipment rely heavily on CNC processes.

Common Misconceptions About Copper Melting Point

Many misunderstandings about copper melting come from mixing visual cues with material science. Copper changes color, softens, and reacts to heat long before it melts. These behaviors lead many engineers, technicians, and buyers to assume copper melts easily or unpredictably. In reality, copper follows clear physical rules that only look confusing when melting point, softening, and boiling are treated as the same concept.

Correcting these misconceptions helps teams avoid unsafe handling, process failures, and incorrect material decisions.

Does Copper Melt Easily?

No, copper does not melt easily—but it can look like it does. Copper glows red at temperatures far below its melting point, which often creates the illusion that melting is imminent. This visual change signals elevated temperature, not phase change.

Key facts to keep in mind:

-

Copper starts glowing red around 525–600 °C

-

It does not begin melting until 1084.62 °C

-

Mechanical strength drops long before melting occurs

This behavior explains why:

-

Copper parts bend or slump without melting

-

Fixtures fail before copper liquefies

-

Surface damage appears even when melting never happens

Softening causes most copper “failures,” not melting. Engineers who design processes around glow color instead of temperature often misjudge safety margins and part stability.

Melting Point vs Boiling Point of Copper

Melting point and boiling point describe completely different physical events. Melting marks the transition from solid to liquid. Boiling marks the transition from liquid to gas. Confusing the two leads to incorrect assumptions about thermal limits.

For copper:

-

Melting point: 1084.62 °C

-

Boiling point: ~2562 °C

This large gap matters in manufacturing:

-

Copper can remain liquid across a wide temperature range

-

Vaporization is not a concern in normal casting or machining

-

Overheating mainly increases oxidation, not boiling risk

Understanding this separation helps teams:

-

Set realistic furnace limits

-

Avoid unnecessary energy input

-

Protect tools and atmospheres from excessive heat

Copper does not “burn” or boil in standard manufacturing environments. Problems at high temperature usually come from oxidation or contamination, not vaporization.

FAQs About Copper Melting Temperature

These questions reflect how engineers, buyers, and technicians actually use copper melting data. They focus on safety, feasibility, and practical limits rather than theory. Clear answers help teams avoid misjudging risk, equipment capability, and process windows.

At What Temperature Does Copper Wire Melt?

Copper wire melts at the same temperature as bulk copper: 1084.62 °C. Wire diameter does not change the melting point. However, thin wire reaches high temperatures faster because it has less thermal mass.

In practice:

-

Thin copper wire softens and sags early

-

Insulation fails long before copper melts

-

Local hot spots can cause deformation without full melting

Electrical failures usually result from overheating and softening, not actual melting of the copper conductor.

Can Copper Be Melted at Home?

Melting copper at home is technically possible but rarely practical or safe. Copper’s high melting point exceeds the capability of most household heat sources.

Key limitations include:

-

Insufficient temperature from common torches

-

Poor temperature control

-

High oxidation risk

-

Serious burn and fire hazards

Home setups often cause:

-

Partial melting

-

Severe oxidation

-

Contaminated copper

For safety and quality reasons, industrial equipment remains the correct environment for melting copper.

Does Copper Melt Before It Glows Red?

No. Copper glows red well before it melts. Visible red glow indicates elevated temperature, not phase change.

Typical behavior:

-

Red glow begins around 525–600 °C

-

Softening accelerates as temperature rises

-

Melting starts only at 1084.62 °C

This gap explains why copper often deforms while still solid. Color alone cannot indicate melting. Reliable temperature measurement is essential.

What Is the Boiling Point of Copper?

Copper boils at approximately 2562 °C under normal pressure. This temperature lies far above standard manufacturing ranges.

For most applications:

-

Copper never approaches boiling

-

Vaporization does not affect casting or machining

-

Oxidation dominates at extreme heat

Understanding this limit reassures engineers that boiling is not a practical concern, even in high-temperature copper processing.

Key Takeaways for Engineers and Buyers

Copper melting point is a reference, not a process guarantee. Copper begins to melt at 1084.62 °C, but real manufacturing outcomes depend on purity, alloy composition, heating rate, and atmosphere. Most production issues occur below the melting point, when copper softens, loses strength, or oxidizes—issues that must be identified and managed through proper inspection and quality control systems

For sourcing and engineering decisions, keep these points in mind:

-

Melting point ≠ usable strength limit

-

Copper alloys melt over a range, not a single temperature

-

Softening and heat transfer drive distortion risk

-

Process selection matters more than the number itself

When teams treat copper melting behavior as a system—not a single value—they reduce scrap, rework, and late-stage design changes.

Related Copper Manufacturing Capabilities and Support

Successful copper parts require the right process, not just the right material. At HM, we support copper and copper-alloy components through process-aware manufacturing, focusing on stability, accuracy, and repeatability rather than trial-and-error. When your design reaches the stage of supplier evaluation or cost validation, you can request a technical quote with your drawings and copper grade specifications

Our capabilities include:

-

CNC machining of copper and copper alloys

-

Process guidance for cast-then-machine strategies

-

Tolerance and surface finish control for heat-sensitive parts

-

Engineering support during material and process selection

If you are evaluating copper for thermal, electrical, or industrial applications, aligning melting behavior with machining and finishing strategy is critical.